On political violence

Charlie Kirk’s death

I was shocked last week as I sat at lunch and heard the news that Charlie Kirk had been shot. I was unfortunate enough to see the horrific video so I knew immediately he was not going to survive.

I immediately condemned the shooting. I passionately condemn all forms of political violence. I condemn those who take to violence to pursue their political goals. I disagree with everything Charlie Kirk stood for, the words he used to hurt others, and his political movement, but nothing about it justifies his horrifying murder no matter who pulled the trigger.

I will leave it to others to discuss his legacy and the hurt that he promulgated against our fellow Americans of color, the LGTBQ community, and his political opponents.

I can hold two thoughts. I don’t believe Charlie Kirk was an American hero and Charlie Kirk should not have been murdered. Those are not mutually exclusive.

I have a reason I feel this way. I actually have several. I want you to understand what’s it is like when violence is the solution.

Colonel Ali

Colonel Ali was the director of the Iraqi Joint Forces Headquarters Public Affairs office. When I first met him in 2005 he was working for another good man and their office was literally a closet in the Iraqi version of the Pentagon. I used the clout I had as their senior advisor and spokesman for Multi-National Security Transition Command-Iraq to get them a proper office and staff.

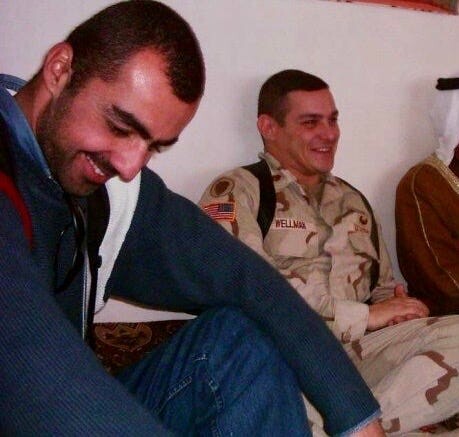

When I returned to Iraq in 2008 he had been promoted to the head of the directorate himself. He was a good man. He had a wonderful sense of humor and an easy smile. We spent countless hours together in Iraq traveling the country visiting Iraqi units.

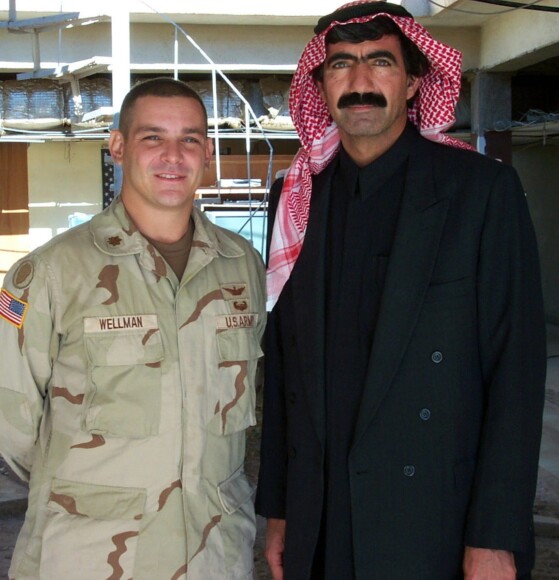

Here we are at the Iraqi Military Academy waiting for our helicopters to come take us back to the Green Zone.

He even visited the United States after I retired from the Army and I had the honor to escort him and his colleagues to Arlington National Cemetery to visit the grave of the remains of U.S. Air Force members and Iraqi Air Force pilots killed in a crash in 2008.

One day Colonel Ali stepped out of his door in Baghdad, kissed his daughter goodbye for the day, and as he turned to walk to his car he was shot multiple times by an assassin riding on the back of a motorcycle who sped off and was never found.

He died on his front walk.

He was my friend.

Lt. Colonel Raad

I first met Sheik Raad when I was stationed at Q-West in southern Ninewa Province. We had arrived there less than a month after the fall of Baghdad. I was the Operations Officer for a UH-60 equipped battalion of the famed 101st Airborne (Air Assault) Division. Within a couple of weeks I found myself visiting local villages and helping them rebuild their lives.

Sheik Raad was the cousin of my closest partner Dr. Muhammed. His village was just outside of my assigned sector – it straddled both the highway from Baghdad to Mosul, the main oil pipeline going north, and astonishingly, the high power electric wires also between the two cities. It was what we call “key terrain.”

Raad looked like he had stepped out of central casting of “Arab warrior.” He was an imposing six foot plus with a dark mustache and striking looks. We used to tease him that he was actually Tom Selleck in disguise.

He was a strong supporter of our efforts and was quickly enlisted by our infantry brigade partners to stand up what they called “Sheik Force” to secure the pipeline and critical infrastructure. He built a small force of his tribe members and they quickly relieved our troops to focus on other areas.

I left in early 2004 and that fall was the infamous “Fall of Mosul” when Al Qaeda in Iraq attacked across the city and region killing hundreds of our allies. The nascent Iraqi Army we had been building at that point almost collapsed completely. Sheik Raad and his men stepped into the breach, secured their area, and turned back the enemy.

We only found later that he has been an Iraqi Special Forces Non-Commissioned Officer in the Iran-Iraq War, so he knew some things. The local U.S. leaders built an entire Iraqi battalion around him and made him a Lt. Colonel like me. I would see him again when I visited his headquarters with my boss, then Lt. General Petraeus.

In 2008 I learned he had been kicked out of the Iraqi Army because they were professionalizing the force and wanted properly trained, educated, and appointed officers only. He hadn’t gone to the military academy and the Americans had installed him in his job. I went to the general of the Iraqi Army’s personnel division to fight for him and got one of the most epic ass chewings of my entire military career by an Iraqi general. Luckily neither of my bosses cared.

I found out in 2014 that at some point the insurgents had placed a bomb in his car and killed him as he left his village.

He was my friend.

Dr. Mohammed

If you’ve followed me for a while you know the story of Dr. Mohammed. We met not long after we arrived at Q-West Airbase. He sent a young boy and an old man with a note to our “gate” to ask for help stopping bullets from landing in their village and with water.

I later asked him why the old man? He said, “well…he had sons already.” I laughed that he was expendable I guess. He shrugged. But why the boy too? “Hopefully you won’t shoot a child.”

An important lesson in Iraqi common sense, I suppose.

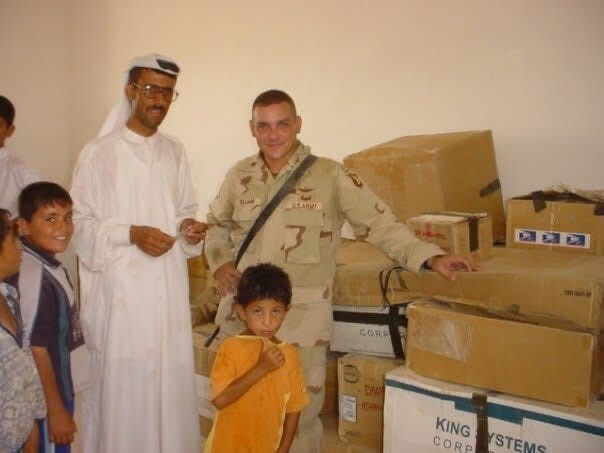

Over the next year we worked hand in hand to meet dozens of villages around the area. We built him a clinic to practice medicine right in his village. Built schools and much more across the area. At one point he told me there was a very large bounty on my head and his for our work.

When I returned to Iraq in 2005 we connected again. He actually came and attended the ceremony when Lt. Gen. Petraeus handed command of my unit over to Lt. Gen. Marty Dempsey with then Lt. Col. Raad. I helped them build a chicken house in their village with reconstruction funds.

He said they would rename the village after me. I scoffed and told him I wanted a statue instead. In 2006 while I was in graduate school at Harvard his vehicle was destroyed by a bomb in the road and he lost both of his legs.

When U.S. forces evacuated Q-West in 2011 two terrorists came to him as patients. Once inside they took out hidden guns and murdered him right in the clinic I had helped build 8 years before.

He was my friend.

Bassam Sabry-Youssef

I met Bassam not long after we started working with the local civilian populace. The 101st Division wanted us all to have assigned interpreters. I met him at a sort of cattle call at my higher headquarters.

Bassam was a mild mannered fellow with a great smile. He and his wife lived in Mosul with their two baby girls. He owned a store near the University of Mosul and was hoping to save enough money to get his family out of Iraq as they were Chaldean Christians and planned to join his extended family in the United States.

He quickly became my right hand man. He didn’t just translate what was said in meetings. He understood the nuance, when someone was lying, and even when we were in danger – a situation that had occurred more than a few times.

One of my favorite stories happened at the end of a long day of visiting villages. There was always a sheik from a nearby one who wanted me to visit and bring the generosity of the U.S. military to their people. It was constant and exhausting.

We were in the southern more….spicy….part of our sector one day when a sheik wanted me to come. I told Bassam to tell him we would be there Thursday at 2:00 PM. He said, “no.”

“Bassam, I’m tired, just tell him the time.”

He replied,”Major Wellman, we don’t know this guy. This is all Batthist around here.”

I said, “I know but Bassam, they are going to cook a sheep and want to know what time.”

Then he gave me the best security advice I ever got in the Army, “Major Wellman, it is better the sheep gets cold, then we get killed.”

I told him to offer “afternoon.” We still went, and we weren’t ambushed.

After I left from my first tour he continued working with my successor. We stayed in touch. Then in late September 2004, I got word he had been kidnapped from his store. The kidnappers were just kids. They took his phone and called his wife to taunt her and the other interpreters he knew. The kidnappers said they were next.

On the third day a video was circulated of him being beheaded on the side of the Tigris River.

He was my dear friend.

I know where this ends

Some may dismiss all of this as not really “political” violence. They are wrong. This is what happens when our differences are settled with violence instead of words. All of these men were good people trying to make their country better and they were ruthlessly murdered for it.

I remember sitting in Dr. Mohammed’s meeting room talking about democracy, dictatorships, and war. I always remember treasuring living in America where these things weren’t the norm,where we had the freedom to vote and violence wasn’t part of the political process.

I can’t say that now, but I hope to God this ends. There is no both sides here as much as some would like us to pretend. The Republicans and MAGA will try to use this to suppress free speech and attack their opponents. They are making those plans now and the orders are coming right from Trump himself.

They want us scared. They want us to shrink from the fight for our democracy.

I’m not scared. I know where this ends if we don’t work to stop it.

It ends with this picture, taken in the clinic that Mohammed would be later murdered in. It’s me and my brothers.

I’m the sole survivor.

I’m not done yet.